(The following review does not contain spoilers; the plot element described below does not appear in the published version of A Devil for

O'Shaugnessy.) In

1973, with his career in decline for more than a decade, Gil Brewer completed a

new noir thriller, A Devil for

O’Shaugnessy. A throwback, the novel would have fit as one of his lesser

Gold Medal paperbacks of the late 1950s, memorable primarily for the appearance

of a deranged pet monkey as a major character. Brewer’s agent submitted the manuscript to Coward, McCann, and the publisher sent detailed suggestions for

revision, including the possibility that “there might be a neater ending in

which Fisk and Miriam are killed together (in a chase scene, for example).”

Brewer dutifully responded to the publisher’s criticisms, only to have his

revision rejected outright. In their kiss-off letter, Coward, McCann made

substantial (and legitimate) objections to aspects of the plot that they had

implicitly endorsed previously. As well, they panned Brewer’s new ending,

complaining that “the car chase, another cliché, seems an awfully familiar

device. Haven’t we seen this already too many times before?” Feel Gil Brewer’s

pain. Grade: C

Sunday, June 23, 2013

Monday, June 17, 2013

Monday, June 10, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

Nobody gets

everything in this life.

You decide

your priorities and

make your choices.

I’d decided

long ago that

any cake I had

would be eaten.

Donald E. Westlake

Two Much!

1975

everything in this life.

You decide

your priorities and

make your choices.

I’d decided

long ago that

any cake I had

would be eaten.

Donald E. Westlake

Two Much!

1975

Sunday, June 9, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, Nobody's Perfect (1977)

I liked the first 89% of Nobody’s Perfect well enough (statistic courtesy of my Kindle’s progress bar) but with 11% to go, Donald E. Westlake lost me. Too much, too silly, too busy, trying too hard. In Nobody’s Perfect, Dortmunder (a.k.a. Sad Sack Parker) has a robbery go unluckily wrong (surprise!) and as a result gets blackmailed into performing another robbery, which, of course, seems unlikely to go well. If you enjoy the Dortmunder formula, you will certainly enjoy Nobody’s Perfect, despite the fact that the book goes to hell at the end—which, given that this is Dortmunder, might actually be the most appropriate possible way for the book to go. Grade: C+

Monday, June 3, 2013

Monday, May 27, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

She said,

“I didn’t ask you

to wait for me.”

“I wasn’t waiting,”

he said.

“I just had

no place to go,

that’s all.”

David Goodis

Down There

1956

Sunday, May 26, 2013

Book Review: Seymour Shubin, Anyone's My Name (1953)

Seymour Shubin began his writing career as an associate

editor for a true-crime magazine, a background that he exploited in his debut

novel, Anyone’s My Name. The novel’s

narrator, Paul Weiler, is true-crime writer whose vocation greases his slippery

slope into crime. Just as the novel’s title promises, Shubin milks the Everyman

theme for every last drop of pathos, but with enough aplomb and cleverness to

earn a spot in the canon of 1950s Noir Well Worth Seeking Out. Grade: A-

Monday, May 13, 2013

Monday, May 6, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

He liked every part of it:

the black look of it,

the short snout of it,

the front sight that could

cut a man’s face like

the tip of a beer-can opener,

the heavy trigger guard,

the curving and rigid grip

of the butt.

James McKimmey

Cornered

1960

Monday, April 29, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

The guilt that separates

man from insects

is not wider than that which severs

the polluted from the chase

among women.

Charles Brockden Brown

Wieland; or The Transformation

1798

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, Jimmy the Kid (1974)

As brilliant as it is self-indulgent, the third Dortmunder novel will delight Westlake fans in general and Parker fans in particular. If you already know anything about Jimmy the Kid, then you already know too much. Read it before you learn more. Grade: A

Monday, April 22, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

it was one thing

to fill four pages

of stupid questions

with on-the-spot lies,

and another thing

to remember

all those lies

ten minutes later

Richard Stark

Butcher’s Moon

1974

Monday, April 15, 2013

Monday, April 8, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, Bank Shot (1972)

In the second Dortmunder novel, Dortmunder steals a bank, and the results are consistently entertaining. The only real flaw in the developing Dortmunder formula is that Westlake has difficulty resisting broad comedy, as when Dortmunder and his crew are closed in the back of a truck with an insidiously bad smell, and will they vomit or won’t they? I imagine that I will keep reading the Dortmunder series until I reach the first fart joke. After that, I may have to stop. Grade: B

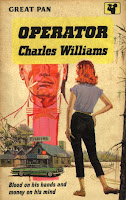

Pulp Poem of the Week

watching me warily and

trying to back away.

I said nothing, and

merely slapped at her again,

feeling a little sick at my stomach.

She was about eighteen.

But it had to be done.

This was the method

they’d left us.

Charles Williams

Talk of the Town

1958

Friday, April 5, 2013

Book Review: James McKimmey, Cornered! (1960)

James McKimmey was in almost the right place at almost the

right time to be counted as one the great writers of noir’s greatest decade,

the 1950s. Had he published his first book with Gold Medal in 1951 (as opposed

to first appearing with Dell in 1958), McKimmey would be mentioned along with

the likes of Charles Williams and Gil Brewer as one of the era’s best, and more

than one of his novels (1962’s Squeeze

Play) would have come back into print by now. The upside to this, however,

is that McKimmey’s OOP books are not exorbitantly expensive, given that they

still fly below most readers’ radar. Cornered!,

from 1960, is well worth seeking out. The plot centers around Ann Burley, an

attractive young woman who provided eye-witness testimony in a California

murder trial and since then has improvised her own less-than-ideal witness

protection program in small-town middle America. The novel gets off to a fast

start when a pair of hoods, who are getting close to finding her, believe that

they have been spotted by law enforcement at a local gas station. Grade: B

Monday, April 1, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

Now that bust-line architecture

has become a basic industry,

like steel and heavy construction,

all the old pleasant conjectures

are a waste of time

and you never believe anything

till the lab reports are in.

Charles Williams

Girl Out Back

1958

has become a basic industry,

like steel and heavy construction,

all the old pleasant conjectures

are a waste of time

and you never believe anything

till the lab reports are in.

Charles Williams

Girl Out Back

1958

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Book Review: Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland; or The Transformation (1798)

An historically important mess is still a mess. Sometimes cited as an early antecedent to noir—but then again, so is Sophocles. Grade: C

Monday, March 25, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

fifteen dollars for a broken jaw,

thirty for a fractured pelvis, and a

hundred for the complete job

David Goodisthirty for a fractured pelvis, and a

hundred for the complete job

“Professional Man”

1953

Monday, March 18, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

A few years more and we’ll be dead

And new faces will come and cackle in this place

Laugh boys laugh

For a heavy doom is awaiting you

Leo Lidz

“A Happy Thought?”

date unknown

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Book Review: Elliott Chaze, Black Wings Has My Angel (1953)

In 2013, Elliott Chaze’s Black

Wings Has My Angel reads like a compendium of noir clichés. This is a partial list:

our narrator/antihero—a WWII vet with a permanent head injury who has a

mutually abusive relationship with a hooker turned femme fatale—is straight out

of Jim Thompson; the armored car heist could come from Richard Stark; the

sadistic smalltown cops might have wandered in from Cornell Woolrich; and the

novel’s intentionally telegraphed sense of doom could be channeled from David

Goodis or Gil Brewer or any of a dozen other Gold Medal novelists. But here’s

the thing: Black Wings Has My Angel

was published in 1953, before these things had become noir clichés

(and when Richard Stark was still nine years away from publishing his first

book). Thus, Elliott Chaze did something truly remarkable: He surveyed the

world of noir, which was just entering its greatest decade; he discerned those

things that made it the blackest; and he blended them into his only noir novel.

And then he walked away. Grade: A-

Monday, March 11, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

aS you think you are youll

Stop meddling in other peoples

affaires pronto and take a

hint from peopl that Shoot

straight. go back to Europe

and stay there We give you

ONE week to Clear out.After

that the 1st warning is

ACID throw in your face but

next time its DIE.

Norman Klein

No! No! The Woman!

1932

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Book Review: Charles Williams, Girl Out Back (1958)

Barney Godwin, a typical noir Everyman, discovers that a local swamp rat has lucked into the proceeds of an infamous back robbery, and he schemes to make the money his own. Girl Out Back should have been better, but author Charles Williams makes little effort to explain the motivations of his first-person narrator, especially early in the novel, and he introduces major plot elements in a lazy hey-guess-what-I-just-remembered fashion. Grade: C

Monday, March 4, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I could come in early

any afternoon

and drink her liquor

and give her a roll in the hay,

no questions asked,

no obligations and

no recriminations.

Not because it was me, either.

It was there for anyone

who was friendly,

no stranger,

and had clean fingernails.

Howard Browne

“Man in the Dark”

1952

Monday, February 25, 2013

Monday, February 18, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I’d trust Andy

alone with my sister

all night long,

if she didn’t have

more than

fifteen cents on her.

Donald E. Westlake

The Hot Rock

1970

alone with my sister

all night long,

if she didn’t have

more than

fifteen cents on her.

Donald E. Westlake

The Hot Rock

1970

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Book Note: Ronald E. Starklake, The Hot Black Ice Rock Score (1968-1970)

I decided to reread The Black Ice Score, a relatively crappy Parker novel, in

the wake of having read the first Dortmunder novel, The Hot Rock. According to author Donald E. Westlake, The Hot Rock came about when a Parker

novel went awry: Parker is anything but a comedic character, and Westlake found

that he was writing Parker into a comedy. Thus, he rewrote the novel with a new

protagonist, Dortmunder, and that novel became The Hot Rock. I repeated this oft-told story in my review of The Hot Rock, prompting a friend to ask

what I made of the existence of The Black

Ice Score, whose premise is eerily similar to The Hot Rock. So I decided to reread The Black Ice Score and think it over.

The Black Ice Score

was first published in 1968; The Hot Rock was

first published in 1970. Both novels are set in New York. Both novels center

around factions from small African nations who compete for ownership of

valuable jewels—an emerald and diamonds, respectively. In both novels, and African faction hires professional American criminals to wrest the jewel(s) from the competing

faction. So what led Westlake to publish such similar novels so close together?

If Westlake’s story of converting the botched Parker novel into the first

Dortmunder novel is true, then this would seem to be the logical sequence of events:

1. Westlake begins writing a Parker novel, but he realizes that the tone is hopelessly wrong, so he stops.

2. Westlake starts the Parker novel over again, maintaining

the proper tone this time, and the result is The Black Ice Score, published in 1968.

3. Westlake, a highly efficient professional writer, hates

to waste anything. He still has the partially (how much?) completed manuscript

from #1, and he wants to do something with it. Therefore, he reworks it into The Hot Rock, published in 1970.

Westlake probably thought it unlikely readers would notice

(or care) about the similarities between Richard Stark’s The Black Ice Score and Donald E. Westlake’s The Hot Rock, so why not? It’s hard to imagine, however, that he

wasn’t asked about this at some point, so if anyone knows anything more, I

would be delighted to hear it.

A footnote: For a Parker fan, the most remarkable moment in The Hot Rock comes in passing, when one

of the professional American thieves, Alan Greenwood, mentions that his current

assumed name is “Grofield.” Alan Grofield, of course, is one of Parker’s

sometime partners, first appearing in The

Score in 1964. So maybe when the abandoned Parker novel became The Hot Rock, Alan Grofield was

transformed into Alan Greenwood? I didn’t pay attention to the initials of the

other thieves in The Hot Rock, but

perhaps they correspond to characters in the Parker novels as well?

Monday, February 11, 2013

Monday, February 4, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I remember that

the fresh earth beside the grave was brown

and wet,

and that

the black coffin was shiny in the sun.

I remember that

I did not cry, but just stood there,

even when the men with the spades went away,

and then, after that,

I do not remember all the things I did that day.

Steve Fisher

I Wake Up Screaming

1941

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Book Review: Richard Stark, Flashfire (2000)

After the Great Parker Hiatus, Ronald Starlake restarted the series with a sequence of linked titles: Comeback, Backflash, Flashfire, Firebreak, and Breakout. Of these five, only Breakout (one of my favorite Parker novels) is distinct in my mind; the others blur together, much as Starklake’s titles suggest that he intended. Thus, when the movie Parker was announced as an adaptation of Flashfire, I couldn’t exactly remember which novel that was, but I chose not to worry about it. I wanted to see the movie on its own terms, so I decided against a pre-screening Flashfire refresher course. Then I went to see Parker, and, much to my surprise, at no point during the movie could I remember anything about Flashfire. The experience was both perplexing and alarming: Is this really an adaptation of a novel that I have read? And, more urgently, am I slipping into some sort of dementia?

For me, the nicest thing about writing these reviews is that I can use them as crutch for remembering what I have read. Therefore, immediately after Parker I went to read my review of Flashfire, and I discovered, to my complete and utter relief and joy, that I had not read it! I had made this mistake because of those dastardly similar titles in combination with my mistaken belief that I owned all of the Parker novels, when in fact I owned all of them but Flashfire. When Flashfire came to the top of the list, I couldn’t read what I didn’t own, so I mistakenly read Firebreak instead. Never have I been happier to be old and easily confused! Only a few weeks ago, I finished the last Parker novel, Dirty Money, and I mourned. But then! lo! a miracle! A new Parker novel (to me, at least!) all but dropped from the heavens!

But what a strange circumstance for reading my (actual) last Parker novel, with Jason Statham and Jennifer Lopez swimming around in my head. Not once while reading Flashfire did I see Jason Statham’s face, but Jennifer Lopez was Leslie Mackenzie. There was nothing I could do about that. Oh, well. The most significant effect that seeing Parker had on my reading of Flashfire is this: Flashfire became a remarkable demonstration that the power of the Parker novels is in the prose, not the plots. The plots, of course, are often brilliant, but while reading Flashfire it was easy to what the movie is missing. You get some of Starklake’s sociopathically stripped language in the dialogue, but where you need it most is in the action, which is precisely where Parker can’t give it to you. So, instead, they give you Parker hanging from a balcony with a knife stabbed completely through his hand—and it’s just not as good. Grade: B-

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)