Monday, April 29, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

The guilt that separates

man from insects

is not wider than that which severs

the polluted from the chase

among women.

Charles Brockden Brown

Wieland; or The Transformation

1798

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, Jimmy the Kid (1974)

As brilliant as it is self-indulgent, the third Dortmunder novel will delight Westlake fans in general and Parker fans in particular. If you already know anything about Jimmy the Kid, then you already know too much. Read it before you learn more. Grade: A

Monday, April 22, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

it was one thing

to fill four pages

of stupid questions

with on-the-spot lies,

and another thing

to remember

all those lies

ten minutes later

Richard Stark

Butcher’s Moon

1974

Monday, April 15, 2013

Monday, April 8, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, Bank Shot (1972)

In the second Dortmunder novel, Dortmunder steals a bank, and the results are consistently entertaining. The only real flaw in the developing Dortmunder formula is that Westlake has difficulty resisting broad comedy, as when Dortmunder and his crew are closed in the back of a truck with an insidiously bad smell, and will they vomit or won’t they? I imagine that I will keep reading the Dortmunder series until I reach the first fart joke. After that, I may have to stop. Grade: B

Pulp Poem of the Week

watching me warily and

trying to back away.

I said nothing, and

merely slapped at her again,

feeling a little sick at my stomach.

She was about eighteen.

But it had to be done.

This was the method

they’d left us.

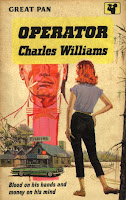

Charles Williams

Talk of the Town

1958

Friday, April 5, 2013

Book Review: James McKimmey, Cornered! (1960)

James McKimmey was in almost the right place at almost the

right time to be counted as one the great writers of noir’s greatest decade,

the 1950s. Had he published his first book with Gold Medal in 1951 (as opposed

to first appearing with Dell in 1958), McKimmey would be mentioned along with

the likes of Charles Williams and Gil Brewer as one of the era’s best, and more

than one of his novels (1962’s Squeeze

Play) would have come back into print by now. The upside to this, however,

is that McKimmey’s OOP books are not exorbitantly expensive, given that they

still fly below most readers’ radar. Cornered!,

from 1960, is well worth seeking out. The plot centers around Ann Burley, an

attractive young woman who provided eye-witness testimony in a California

murder trial and since then has improvised her own less-than-ideal witness

protection program in small-town middle America. The novel gets off to a fast

start when a pair of hoods, who are getting close to finding her, believe that

they have been spotted by law enforcement at a local gas station. Grade: B

Monday, April 1, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

Now that bust-line architecture

has become a basic industry,

like steel and heavy construction,

all the old pleasant conjectures

are a waste of time

and you never believe anything

till the lab reports are in.

Charles Williams

Girl Out Back

1958

has become a basic industry,

like steel and heavy construction,

all the old pleasant conjectures

are a waste of time

and you never believe anything

till the lab reports are in.

Charles Williams

Girl Out Back

1958

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Book Review: Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland; or The Transformation (1798)

An historically important mess is still a mess. Sometimes cited as an early antecedent to noir—but then again, so is Sophocles. Grade: C

Monday, March 25, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

fifteen dollars for a broken jaw,

thirty for a fractured pelvis, and a

hundred for the complete job

David Goodisthirty for a fractured pelvis, and a

hundred for the complete job

“Professional Man”

1953

Monday, March 18, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

A few years more and we’ll be dead

And new faces will come and cackle in this place

Laugh boys laugh

For a heavy doom is awaiting you

Leo Lidz

“A Happy Thought?”

date unknown

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Book Review: Elliott Chaze, Black Wings Has My Angel (1953)

In 2013, Elliott Chaze’s Black

Wings Has My Angel reads like a compendium of noir clichés. This is a partial list:

our narrator/antihero—a WWII vet with a permanent head injury who has a

mutually abusive relationship with a hooker turned femme fatale—is straight out

of Jim Thompson; the armored car heist could come from Richard Stark; the

sadistic smalltown cops might have wandered in from Cornell Woolrich; and the

novel’s intentionally telegraphed sense of doom could be channeled from David

Goodis or Gil Brewer or any of a dozen other Gold Medal novelists. But here’s

the thing: Black Wings Has My Angel

was published in 1953, before these things had become noir clichés

(and when Richard Stark was still nine years away from publishing his first

book). Thus, Elliott Chaze did something truly remarkable: He surveyed the

world of noir, which was just entering its greatest decade; he discerned those

things that made it the blackest; and he blended them into his only noir novel.

And then he walked away. Grade: A-

Monday, March 11, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

aS you think you are youll

Stop meddling in other peoples

affaires pronto and take a

hint from peopl that Shoot

straight. go back to Europe

and stay there We give you

ONE week to Clear out.After

that the 1st warning is

ACID throw in your face but

next time its DIE.

Norman Klein

No! No! The Woman!

1932

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

Book Review: Charles Williams, Girl Out Back (1958)

Barney Godwin, a typical noir Everyman, discovers that a local swamp rat has lucked into the proceeds of an infamous back robbery, and he schemes to make the money his own. Girl Out Back should have been better, but author Charles Williams makes little effort to explain the motivations of his first-person narrator, especially early in the novel, and he introduces major plot elements in a lazy hey-guess-what-I-just-remembered fashion. Grade: C

Monday, March 4, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I could come in early

any afternoon

and drink her liquor

and give her a roll in the hay,

no questions asked,

no obligations and

no recriminations.

Not because it was me, either.

It was there for anyone

who was friendly,

no stranger,

and had clean fingernails.

Howard Browne

“Man in the Dark”

1952

Monday, February 25, 2013

Monday, February 18, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I’d trust Andy

alone with my sister

all night long,

if she didn’t have

more than

fifteen cents on her.

Donald E. Westlake

The Hot Rock

1970

alone with my sister

all night long,

if she didn’t have

more than

fifteen cents on her.

Donald E. Westlake

The Hot Rock

1970

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Book Note: Ronald E. Starklake, The Hot Black Ice Rock Score (1968-1970)

I decided to reread The Black Ice Score, a relatively crappy Parker novel, in

the wake of having read the first Dortmunder novel, The Hot Rock. According to author Donald E. Westlake, The Hot Rock came about when a Parker

novel went awry: Parker is anything but a comedic character, and Westlake found

that he was writing Parker into a comedy. Thus, he rewrote the novel with a new

protagonist, Dortmunder, and that novel became The Hot Rock. I repeated this oft-told story in my review of The Hot Rock, prompting a friend to ask

what I made of the existence of The Black

Ice Score, whose premise is eerily similar to The Hot Rock. So I decided to reread The Black Ice Score and think it over.

The Black Ice Score

was first published in 1968; The Hot Rock was

first published in 1970. Both novels are set in New York. Both novels center

around factions from small African nations who compete for ownership of

valuable jewels—an emerald and diamonds, respectively. In both novels, and African faction hires professional American criminals to wrest the jewel(s) from the competing

faction. So what led Westlake to publish such similar novels so close together?

If Westlake’s story of converting the botched Parker novel into the first

Dortmunder novel is true, then this would seem to be the logical sequence of events:

1. Westlake begins writing a Parker novel, but he realizes that the tone is hopelessly wrong, so he stops.

2. Westlake starts the Parker novel over again, maintaining

the proper tone this time, and the result is The Black Ice Score, published in 1968.

3. Westlake, a highly efficient professional writer, hates

to waste anything. He still has the partially (how much?) completed manuscript

from #1, and he wants to do something with it. Therefore, he reworks it into The Hot Rock, published in 1970.

Westlake probably thought it unlikely readers would notice

(or care) about the similarities between Richard Stark’s The Black Ice Score and Donald E. Westlake’s The Hot Rock, so why not? It’s hard to imagine, however, that he

wasn’t asked about this at some point, so if anyone knows anything more, I

would be delighted to hear it.

A footnote: For a Parker fan, the most remarkable moment in The Hot Rock comes in passing, when one

of the professional American thieves, Alan Greenwood, mentions that his current

assumed name is “Grofield.” Alan Grofield, of course, is one of Parker’s

sometime partners, first appearing in The

Score in 1964. So maybe when the abandoned Parker novel became The Hot Rock, Alan Grofield was

transformed into Alan Greenwood? I didn’t pay attention to the initials of the

other thieves in The Hot Rock, but

perhaps they correspond to characters in the Parker novels as well?

Monday, February 11, 2013

Monday, February 4, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I remember that

the fresh earth beside the grave was brown

and wet,

and that

the black coffin was shiny in the sun.

I remember that

I did not cry, but just stood there,

even when the men with the spades went away,

and then, after that,

I do not remember all the things I did that day.

Steve Fisher

I Wake Up Screaming

1941

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Book Review: Richard Stark, Flashfire (2000)

After the Great Parker Hiatus, Ronald Starlake restarted the series with a sequence of linked titles: Comeback, Backflash, Flashfire, Firebreak, and Breakout. Of these five, only Breakout (one of my favorite Parker novels) is distinct in my mind; the others blur together, much as Starklake’s titles suggest that he intended. Thus, when the movie Parker was announced as an adaptation of Flashfire, I couldn’t exactly remember which novel that was, but I chose not to worry about it. I wanted to see the movie on its own terms, so I decided against a pre-screening Flashfire refresher course. Then I went to see Parker, and, much to my surprise, at no point during the movie could I remember anything about Flashfire. The experience was both perplexing and alarming: Is this really an adaptation of a novel that I have read? And, more urgently, am I slipping into some sort of dementia?

For me, the nicest thing about writing these reviews is that I can use them as crutch for remembering what I have read. Therefore, immediately after Parker I went to read my review of Flashfire, and I discovered, to my complete and utter relief and joy, that I had not read it! I had made this mistake because of those dastardly similar titles in combination with my mistaken belief that I owned all of the Parker novels, when in fact I owned all of them but Flashfire. When Flashfire came to the top of the list, I couldn’t read what I didn’t own, so I mistakenly read Firebreak instead. Never have I been happier to be old and easily confused! Only a few weeks ago, I finished the last Parker novel, Dirty Money, and I mourned. But then! lo! a miracle! A new Parker novel (to me, at least!) all but dropped from the heavens!

But what a strange circumstance for reading my (actual) last Parker novel, with Jason Statham and Jennifer Lopez swimming around in my head. Not once while reading Flashfire did I see Jason Statham’s face, but Jennifer Lopez was Leslie Mackenzie. There was nothing I could do about that. Oh, well. The most significant effect that seeing Parker had on my reading of Flashfire is this: Flashfire became a remarkable demonstration that the power of the Parker novels is in the prose, not the plots. The plots, of course, are often brilliant, but while reading Flashfire it was easy to what the movie is missing. You get some of Starklake’s sociopathically stripped language in the dialogue, but where you need it most is in the action, which is precisely where Parker can’t give it to you. So, instead, they give you Parker hanging from a balcony with a knife stabbed completely through his hand—and it’s just not as good. Grade: B-

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Book Review: Donald E. Westlake, The Hot Rock (1970)

This is less a review of the first Dortmunder novel than a first reaction to the existence of the Dortmunder series. When I finished the last of Donald E. Westlake’s twenty-four Parker novels, I turned to Dortmunder as a possible replacement in my reading program. As the well-known story goes, Westlake wrote the first Dortmunder novel when a Parker novel went awry, becoming too humorous to work as a vehicle for the sociopathically humorless Parker (though Parker does drop a few seemingly intentional one-liners in the later books of the series—a remarkable sign of growth in a generally static character). I love humor, but I love the humorless Parker more, so while I was reading The Hot Rock, I was wishing the whole time that it were a Parker novel. That’s just me. Dortmunder came as advertised: He’s a sad-sack Parker who moves through a world of absurdity rather than a world of menace. I often see the Dortmunder novels described as comic, but I would opt to describe The Hot Rock as silly. I enjoyed the silliness (given that silly Parker is better than no Parker), and as I make my way through the rest of the series, I will be interested to see if Westlake can ever manage any of the profundity with silly that he manages with menacing. To be sure, it’s a more difficult task. Grade: B

Monday, January 28, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

Excitement and

expectation and

her skill

finished him almost at once.

He lay startled and

humiliated and

enraged:

the boy who got to the movie

just as it was ending.

Richard Stark/Darwyn Cooke

The Hunter

1962/2009

Labels:

Darwyn Cooke,

Donald E. Westlake,

Richard Stark

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Book Review: Steve Fisher, I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Steve Fisher wastes a truly memorable character, noir cop Ed Cornell, in this name-dropping Hollywood whodunit, which is amateurishly plotted and overrun with italics and exclamation points. When the excitement builds, you will know it for sure! Grade: C

Monday, January 21, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

seldom attract

the type of men

which their successful

pursuit demands

Jim Thompson

The Golden Gizmo

1954

Monday, January 14, 2013

Pulp Poem of the Week

I tried to give him

the finger,

but I think I was too tired

to lift my hand.

Dave Zeltserman

A Killer’s Essence

2011

the finger,

but I think I was too tired

to lift my hand.

Dave Zeltserman

A Killer’s Essence

2011

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Book Review: Darwyn Cooke, The Hunter (2009)

Sometimes I react to a graphic novel by mumbling “I guess it

was pretty good,” and this is one of those times. Having come to graphic novels

too late in life, I often feel cut off from enjoying the art form, and, as a

Parker fan, I have a hard time understanding why someone would work so hard at

illustrating a detailed outline of a Parker novel, unless it’s to exploit a

market of people who would never read a not-graphic Parker novel. This adaptation is well done (I guess), and I enjoyed seeing how Darwyn Cook chose

to illustrate Parker himself. The page where Parker’s face first appears is

quite arresting—he’s sort of a cross between Clark Kent and the Manhunt apeman. His face is, I think, too

pretty, but this may well change with Parker’s plastic surgery. So, curious to

see how the post-surgery Parker looks, I do plan on reading the next adaptation

in the series (I guess). Grade: B

Labels:

Darwyn Cooke,

Donald E. Westlake,

Richard Stark

Monday, January 7, 2013

Sunday, January 6, 2013

Book Review: Richard Stark, Dirty Money (2008)

The final Parker novel,

Dirty Money, is good in the ways that all Parker novels are good, but there

is nothing otherwise remarkable about it. It picks up right where the previous

Parker novel leaves off: Our antihero wants to retrieve the $2 million dollars

that his gang left hidden at the end of Ask

the Parrot. He wants this money even though he knows that it is marked and

therefore useless in the United States. This is a desperate Parker, running low

on cash and working without I.D. Thus, his larger goal in the novel is to

become a fully functional Parker again, flush and not fearful of an ordinary

traffic stop. When Parker achieves this goal, however, the victory feels

unavoidably sad, and I’m not too noir to admit it: I felt choked up at the end,

sentimental about the exit of a character whose great charm is that he never feels

sentimental. Grade: B-

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Book Review: Dave Zeltserman, A Killer's Essence (2011)

Dave Zeltserman’s A

Killer’s Essence put me in mind of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s notion of a

Romance. In his preface to The House of

the Seven Gables (1851), Hawthorne explained, “When a writer calls his work a Romance, it need hardly

be observed that he wishes to claim a certain latitude, both as to its fashion

and material, which he would not have felt himself entitled to assume had he

professed to be writing a Novel. The latter form of composition is presumed to

aim at a very minute fidelity, not merely to the possible, but to the probable

and ordinary course of man's experience. The former—while, as a work of art, it

must rigidly subject itself to laws, and while it sins unpardonably so far as

it may swerve aside from the truth of the human heart—has fairly a right to

present that truth under circumstances, to a great extent, of the writer's own

choosing or creation. If he think fit, also, he may so manage his atmospherical

medium as to bring out or mellow the lights and deepen and enrich the shadows

of the picture. He will be wise, no doubt, to make a very moderate use of the

privileges here stated, and, especially, to mingle the Marvelous rather as a

slight, delicate, and evanescent flavor, than as any portion of the actual

substance of the dish offered to the public.” At its core, A Killer’s Essence is a police

procedural, which is to say, a Novel. In the Novel’s main plotline, NYC cop

Stan Green grasps at threads to catch a serial killer. The evanescent flavor of

the Marvelous is provided by Zachary Lynch, a witness to one of the killer’s

crimes. Lynch is a semi-recluse with neurological damage that prevents him from

seeing faces. Instead, he sees the essence of people’s souls, be they serial

killers or cops. As always, Zeltserman gives readers what they expect from a

crime novel—and then a little bit more. Grade: B

Monday, December 31, 2012

Pulp Poem of the Week

People who think

That yelling and screaming

Are the same thing

That yelling and screaming

Are the same thing

Have never screamed.

David Rachels

Verse Noir

2010

Monday, December 24, 2012

Pulp Poem of the Week

Mme Ernestine Gapol,

49,

dwelling in Vanves,

on Avenue Gambetta,

committed suicide:

two bullets in the head.

Félix Fénéon

Novels in Three Lines

1906

(translated by Luc Sante)

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Book Review: Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye (1953)

In a 1945 letter, Raymond Chandler wrote that “it doesn’t

matter a damn what a novel is about, that the only fiction of any moment in any

age is that which does magic with words.” In 1947, he wrote that he was

“fundamentally rather uninterested in plot” and that “the most durable thing in

writing is style.” In 1953, Chandler showed that he meant it when he published The Long Goodbye, which was 47% longer

than his previous Philip Marlowe novel, 1949’s The Little Sister. This extra 47% is almost all style—or, if you

prefer, padding. If you agree with Chandler that “it doesn’t matter a damn what

a novel is about,” then you will likely think that The Long Goodbye is his masterpiece. If you disagree, then you will

likely find the book self-indulgent. I tend toward the latter camp. Marlowe is

still Marlowe, but all the extra style gives him the chance for even more

self-righteous speechifying than usual, rather as if he is pointing the way for

John D. MacDonald to invent Travis McGee. In sum, I can read any page in The Long Goodbye with great pleasure,

but there’s just too damn many of them. Grade: B

Monday, December 17, 2012

Sunday, December 16, 2012

Book Review: Kenzo Kitakata, City of Refuge (1982)

Twenty-one-year-old Koji Mizui’s life spins out of control:

his girlfriend turns out to be a minor; he (sort of) loses his job after

spending time in jail falsely arrested; he kills one man, and then another, in

semi-self-defense. As a result, he ends up running from the mob and the police,

travelling with an abandoned six-year-old to whom he becomes a surrogate

father. In sum, noir crossed with a buddy movie crossed with Sesame Street. City of Refuge tries to be moving but ends up bland. Grade: C+

Monday, December 10, 2012

Pulp Poem of the Week

Well.

The first impression was of

a slender, stylish, well-put-together

woman in her forties,

but almost instantly

the impression changed.

She wasn’t slender;

she was bone thin,

and inside the stylish clothes

she walked with a graceless

jitteriness,

like someone whose medicine

had been cut off too soon.

Beneath the neat cowl of

well-groomed ash-blond hair,

her face was too thin,

too sharp-featured,

too deeply lined.

This could have

made her look haggard;

instead,

it made her look mean.

From the evidence,

what would have

attracted her husband

would have been

her father’s bank.

Richard Stark

Nobody Runs Forever

2004

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)